The sound of the Drummer’s beat

The Castiles – Brucebase Wiki

July 1 – August 4, 1965

As their oath will tell you, the Official Court Reporters are “guardians of the record,” and, as such, they must remain neutral and professional at all times. Displaying expressions like surprise, judgment, or sympathy could signal bias toward one of the parties, which is a serious ethical violation that undermines the integrity of the legal process.”

I was always seated up in front of the witness stand. I enjoyed my position to be also facing the judge – you know, having him or her within my direct vision and hearing range during the trial with just a twitch or a blink of my eyes or a slight turn of my head. And, of course, I needed to be watching the lawyer who was questioning the witness, who, as I said, was seated directly in front of me. The lawyer typically would be on the opposite side of my view of the judge. Still, I liked to have also the jury in front of me, in my view while they watched the witness speak. This way not only could I see the expressions on the faces of the members of the jury as they listened to the attorney’s questions, the judge’s statements and rulings, but I could also watch them see the witness’ responses to the questions with just a quick glance, if I desired to do so.

Meanwhile, from my vantage point, I could view the lips of the witness up close, and it was through this practice that I learned to read lips on a very rudimentary basis. Comparing what they said to the expression of their eyes was always a telltale game I practiced as they spoke. As their facial features changed with their spoken words, I could detect the truth or non-truth to their testimony. Also, I was able to watch the reaction of the people who were judging their words and who would ultimately render a verdict based on what the witnesses were claiming to be the situation before them.

Me? Right. I could not indicate my own feelings about anything I was seeing or hearing. And for all those years I did not. Not once. On purpose, that is. At least not that I know of. I never had a complaint. Let’s put it that way. Not even when a female juror kept looking at me, eyeing me, and pointing to the middle of her bosom and then surreptitiously pointing at me, to my own breast, with her forefinger; and when I looked down at my chest, she then smiled. How strange, I thought. Finally, still attempting to concentrate on the testimony, lo and behold, I saw it! There was a bone – that’s what was pinching me, I thought, the whole time. A bone is what it was called then, the underwire of my bra, and it was sticking out of my blouse! It had torn through the fabric of my bra and managed to make its way out between the opening of the buttonhole of my striped shirt and was aiming up toward my throat. Yikes! I was about to be harpooned, right there in the courtroom in front of everyone.

So, between a pause of the witness’ words, I casually reached up with my hand and nonchalantly tucked it back inside my shirt all without moving a facial muscle. Like, you know, thank you, Ms. Juror, and, like, you know, how terribly funny and embarrassing was that! I bet that juror had a story to tell her family that night.

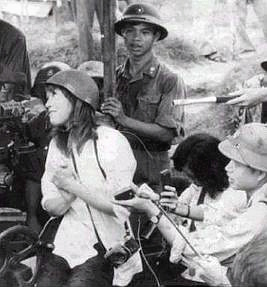

Anyway, not ever except one time, did I lose control and squint disapproval at a witness. Instantly I realized I was slowly shaking my head from left to right and the reverse! And it was not at what the witness was saying but at the witness herself. And, believe me, I did the “wrong” thing. My mind strayed. And instead of listening to what she was saying and writing on my steno machine exactly what she was saying, I was thinking about what she did many years ago.

This was happening right then while the witness was testifying up on the stand less than three feet in front of me. All I could think of doing was stand up, reach over, and like a child, grabbing her by her shoulders and saying, “Why did you do it, Jane? Why?”

Let me back up a moment.

In my mid-teens, in Jr. High School, I learned to jitterbug in Barbara’s basement in Elberon, and then I would try to dance in the gym waiting to practice with the cheerleaders. Then one evening I entered an establishment in the summer of ‘66 in Asbury Park, New Jersey. It was the place to be at that time. The bouncer looked away from my I.D. and allowed me to pass. Not so now looking at my 80-year old driver’s license, though. How come? They don’t even ask to see it anymore. But have you noticed recently, the older you are, the younger the kids look?

Back then, once inside that new world, holding my very weak Screwdriver, my girlfriend taught me the nightclub dances right there on the floor – you know, hands in the air type dancing, a more free-style form of dancing of the day — or, I mean, of the night. This was at the same time my brother was waiting in line an extraordinarily long time and was successful to find himself on TV dancing to the tunes on American Bandstand. Like, how proud I was! And here I am in Asbury Park teaching myself where the best place was to stand to feel – and you know what? It was standing directly by the drummer where you can feel the floor vibrate from the crashing of his drumsticks. And that’s where you would find me all night. That night and whenever I’d return. I found my freedom there through the sound of the beating of that drummer who would smile back at me when I took my spot in front of him. No, it wasn’t anyone famous like Dick Clark, but I was happy just releasing pent-up energy from sitting in the courtroom 9 to 5.

Now, this was around 1966 when Bart Haynes, the drummer for the Castiles, one of Bruce Springsteen’s earliest bands, joined the Marines. He was sent to Vietnam in April 1967. And after receiving a purple heart for his injuries sustained during a patrol boat mission, which was caused by enemy action, Lance Corporal Barton Edward Haynes was later killed by mortar fire near Quang Tri, South Vietnam, on October 22, 1967.

I didn’t know his name way back when my brother was dancing on American Bandstand in Philly. In fact, I was dancing to a different drummer by then. But I was nearby living in the same cultural current, moving to the same music, learning to dance right in front of this new drummer, be it a little below the small stage. Thanks to Prof. Melissa Ziobro, this past week I learned all about Bart Haynes and the beat of his drums. What’s important here is that Bart’s drumbeat didn’t stop. It had just changed tempo. Then I moved away to L.A., and for me it stopped altogether. For years.

I’ve always felt connected to rhythm, having played a few instruments myself – violin, organ, and banjo (the first was in the orchestra and with private lessons; the rest were self-taught. Just don’t ask me to sing for I cannot carry a tune. As a small child, my mother used to put me on the dining room table after a big holiday meal to entertain the guests. No, they weren’t applauding, I didn’t know that – they were clapping and laughing. Do I have a personality defect? You betcha! Today, even my parrots seem to run and hide when I sing to them. The African Grey would twitch her head when I try to hit high notes – wait, is that what the violin instructor used to do when he asked to sing the note first? But maybe the rhythm thing is because my father’s Wolverine athletic family and friends who served in WWII, would tell stories; I learned about their sacrifices – away from family and friends, physical harm, and death, about their silence, and surely times of survival. I learned to push onward, to find balance. The war shaped my dad, you see, and in turn it shaped me. I discovered, as I wrote my book about their legacy, that the pounding on the drums or the repetition of the drumbeat isn’t always loud — it’s often a quiet pulse beneath everything we do.

Decades later, I found myself in federal court, keeping that same vow, sworn to show no bias by any means of expression whatsoever. I kept to this pledge for 30 years, and the one time I did not, I don’t believe anyone noticed except me. Hopefully, the witness did. I was slowly shaking my head while looking at her. And it took all I could to keep from muttering out loud: Why did you do it, Jane? Seeing her just stirred something deep inside of me that I didn’t realize was there. Yes, I kept my oath for all those years—never flinched, never cracked, never smirked, never raised an eyebrow. But that day, as she spoke, my head moved before I could stop it. Not in defiance. But in recognition. In grief. In truth. Again, folks, I didn’t speak. I didn’t interrupt. I just shook my head. And in that quiet motion, I heard the echo of every drumbeat I’d ever danced to, and every silence between the sounds of war, every promise I’d ever sworn to uphold. Next, I stopped shaking my head and I bowed it.

Some people live by the beat of the world around them. Me? Back then I learned to dance to a different drummer. And sometimes that drum’s rhythm leads me straight into memory.

Photo credit: Wikipedia, Hanoa Jane, Vietnam