Stained glass window memorial, commemorating the 3rd Air Division, inside the church of St Andrew and St Patrick, Elveden, Suffolk. Source: UPL 71561 | American Air Museum

Operation Zebra: Daylight Over France

On June 25, 1944, the U.S. Eighth Air Force’s 3rd Air Division launched Operation Zebra, the first large-scale daytime supply drop to the French Resistance. In total, 180 B-17 bombers, flying in groups of 36 and escorted by USAAF Mustangs and Thunderbolts, delivered 2,160 containers of arms and supplies to Maquis units at four locations—Ain, Jura, Haute Vienne, and Vercors. The mission was a resounding success and marked a pivotal shift in Allied support strategy.

Background: From Night to Day

Until mid-1944, Allied air drops to resistance fighters were conducted strictly at night, under a full moon for better vision, it was reported, often limited to a dozen containers or fewer. These missions, timed with those full moons and managed by the RAF and USAAF’s “Carpetbagger” squadrons, prioritized stealth but strained under rising demand —particularly after the FFI’s (Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur) official mobilization on June 6, 1944.

The 801st Bomb Group—nicknamed the Carpetbaggers—pioneered these nocturnal drops using modified, black-painted B-24 Liberators equipped with radar, flash-suppressed guns, and adapted bomb bays for parachute containers and agents. Flying below 2,000 feet and evading German radar, the crews faced steep odds. Early missions had high failure rates, and even as effectiveness improved, questions lingered: Were supplies reaching the right hands? Were they intact?

Only twenty-eight of seventy-six operational sorties were successful. “Success” was defined as containers dropped and the plane returned. The crew never knew if they dropped supplies to a German-controlled group, or if the supplies were undamaged. By March, the ratio had improved with forty-four of seventy-two sorties successful.

See: v3n1_supplying_resistance.pdf

Between January and March 1944, despite improvements, the limitations of moonlit flights made clear that night drops alone couldn’t meet the Resistance’s mounting needs.

The Eighth Air Force (8th AF) emblem is a blue disc with a winged numeral “8” in the center, a white five-pointed star, and a red disk in the lower loop of the “8”. The emblem was designed by former Air Force Major Ed Winter of Savannah, Georgia. The design was approved on May 20, 1943, but the wings were originally upswept. On June 5, 1943, the final design was approved with the wings in a more “V” shape, likely at the request of General Ira C. Eaker, who commanded the 8th AF at the time. Both versions of the emblem are considered correct, as photos show Eaker wearing both during the war.

The 8th AF was a combat air force in the European theater of World War II, from 1939–1945. During this time, the 8th AF was the largest combat air force in the U.S. Army Air Forces in terms of personnel, equipment, and aircraft. The 8th AF was known as the “Mighty Eighth” because of its ability to launch more than 2,000 bombers and 1,000 fighters on a single mission, and its impressive record during the war. However, the 8th AF also suffered the most casualties of any U.S. Army Air Forces unit in World War II, with more than 26,000 deaths.

Planning a New Approach

Henri Ziegler, FFI chief of staff, urged Allied command to consider mass daylight drops to ensure greater volume and accuracy. SHAEF and the Eighth Air Force agreed. By mid-June, SOE agents and Maquis leaders were scouting potential drop zones, confirming ground readiness, and preparing to retrieve and conceal supplies at scale. (During World War II, the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the Maquis were two groups that collaborated to fight the Nazi occupation of France. The SOE agents worked with resistance groups to boost morale and aid local resistance movements. The Maquis were small groups of armed people who conducted guerrilla warfare in rural areas of France. )

Operation Zebra, launched June 25, was the first of four massive daylight drops, followed by Operations Cadillac, Buick, and Grassy in July, August, and September. In each, hundreds of bombers delivered thousands of containers—often coordinated via coded BBC broadcasts and marked by ground signal fires. These missions were risky, but morale-boosting. One resistance message reportedly praised the Allies for “a damned good show.”

Across the four operations, over 800 B-17 sorties dropped nearly 2.7 million pounds of material. Though German retaliation followed, especially in Vercors, the overall effect was transformative. (It was in Vercors, that at the end of June the Germans continued with several more probing attacks as a result of these operations. The maquis received more parachuted arms and supplies from the Allies, along with an OSS team of 15 American soldiers and a four-man SOE team.) As one Maquis leader reportedly put it: “We now consider this area to be well armed.”

French civilians observe USAAF B-17s dropping supplies on 14 July 1944 (Bastille Day) during Operation CADILLAC.

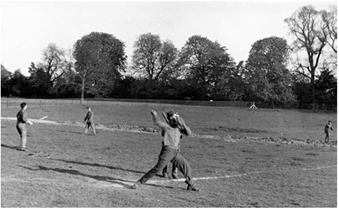

Like soldiers everywhere, the OSS personnel at Area H spent their free time relaxing – either it was that or they were on KP. SE France 1944