Drum, Drummers, Drumbeats

It was just the other day – well, a couple months and 81 years ago, on August 29, 1944, when 15,000 American troops of the United States Army’s 28th Infantry Division, led by the French 2nd Armored Division, were seen by what appeared to be zillions of euphoric people marching down the Champs-Élysées to continue a celebration of the liberation of Paris from Nazi occupation. This enormous parade, joined by the sounds of clamorous people and celebratory music, occurred

only days after there was a formal liberation of the city on August 25, 1944. This parade demonstrated not only a sign of hard earned victory, but it was a display of force.

This breathtaking spectacle of Allied troops parading through Paris, the beating heart of France, proved to be the most powerful symbol of hope for the people and their resistance to the forced takeover by the Nazi regime.

Source: YouTube Freeze image of the French 2nd Armored Division band

August 29,1944? (question mark theirs) from: Bing Videos

It wasn’t just a military victory – it was a cultural and emotional turning point. The sight of Allied troops parading through the heart of France was a powerful symbol of their resilience and resistance. The people lined up along the streets of Paris were not just seeing a parade. They were hearing it. And what exactly were they hearing? Most predominantly, they were hearing drums, don’t you think? Well, maybe along with the screaming and cheering of the crowds. Consider this. Along with the yelling for freedom above the trumpets and bugles, think about those musical instruments. What else do you hear and sometimes don’t even realize it? But you certainly feel it. It’s the drums. It’s the vibration. The drum is a powerful tool: it heals, it communicates, and it transforms. Throughout history, we have seen – and heard! – it used; seen for it’s clean, sharp look and color, too. More importantly, it helps all the musicians to keep the same time and keep the same rhythm with the music they’re playing. And to them it really feels good.

In the line of musical instruments, though, drums are said to be the world’s oldest. Its basic design has been practically unchanged for thousands of years. Drums are dated back to a period of 5500-2350 BC in China alone. Chinese troops used tàigǔ drums to motivate their troops – they called out orders and announcements and to help set a marching pace. There is a story about how these drums even changed the morale of their troops in a major battle in China. It’s a mental thing. Here’s how it goes:

The tale of the Battle of Changshao, which took place in 684 BC. In the story, the Duke of Lu and his strategist Cao Gui use the timing of the war drums to outmaneuver the larger, more powerful army of the State of Qi. This story perfectly illustrates the use of taigu drums to influence morale and win a battle.

The story of the Battle of Changshao demonstrates that victory is not just about a large army, but about understanding and manipulating the morale and psychology of one’s soldiers. It highlights how the disciplined, patient use of the war drum was a key strategic tool.

See: How drumbeats won the battle of Changshao | Hindustan Times

The Ottoman Turks had their elite military bands with the mehter who mounted timpani-like drums on the back of their horses or even camels. (Those poor animals!) The drums were paired with trumpeters and announced the arrival of the armies. Both the trumpeters and the timpanists were highly regarded and, thus, often were placed close to the commanding officer during battle. The mehter bands always played in the battlefields yelling “Yektie Allah” (meaning God is the only one). And to keep the army guards awake, you’d hear them playing at night. They stood next to the Sultan and the soldiers. “They started to play to increase the soldiers’ courage.”

See: Motivating the Army with Music: Mehterân – Motley Turkey

The sound associated with the mehterân also exercised an influence on European classical music, with composers such as Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and Ludwig van Beethoven all writing compositions inspired by or designed to imitate the music of the mehters.

Ottoman military band – Wikipedia

Image source: Mehter davul – Ottoman military band – Wikipedia

Later in the 19th century in West Africa, percussion instruments were adopted for use by their various armies. For example, the Junjung and Tama drums were used as communication and military purposes by the West African Serer people. Their significant roles were seen at ceremonies contributing to the morale and discipline of their troops. From a historical perspective, they were also beaten when the kings wanted to address their followers and also on special occasions in Serer country.

You know, I can’t give a thorough history of drums because throughout the world ancient drums can be found in bas-reliefs, in relief sculptures, and in artifacts. Many articles and books have been written on the subject. Humans devised ways to make their drumheads from animal skins, crafting their drums from pottery, wood, and gourds. The earliest percussion instruments didn’t just even have a stretched head but included idiophones like sticks, hollow logs, or rattles. Examples of these can be found everywhere throughout the globe. If a society was found to have drums, it meant it was communicating, that its people were using them as tools, conveying messages and planning community activities. Think about drums as being a universal language, “transcending linguistic barriers and facilitating the exchange of information across vast distances.”

See: A Brief History of Drums: From Ancient Times to Modern Era – London Drum Institute

Communication via drums was seen by many cultures to be important in warfare, not just as a social communicator. The Chinese placed drummers on the battlefields for hundreds of years; then, thanks to the Ottomans, they were seen in Europe as a communication device in their military armies. The drummers used their instruments to send signals via the officers to their troops. This was occurring all over the world by the latter part of the 18th Century. We can talk about ancient, middle age and modern drums forever, but this is merely a blog and an intro into drummers. Here I want to move on to who played those drums during battle.

In our early wars drummers could enlist. In some areas, a big benefit to enlisting was the wage of a guaranteed $12 a month, with an enlistment bounty of about $50. This certainly appealed to orphans, children from poor families, and paperboys with poor pay. Drummers were recruited to send signals via their drumbeats. The youngest American boy playing the drums was in the American War of Independence, and he was seven years old! Others have been noted to be 12 years old and on up to 19. Not only playing their drums, but they were also charged with learning all the tunes of the different commands (so were the listening troops) plus helping with medical aid and surgeries on the front lines. Unfortunately, as communicators of commands, they were prime targets and died right there on the battlefields of our earth.

Typically, the drummers moved to the rear and stayed away from the shooting once the fighting began. But the Civil War battlefields were terribly dangerous places, and drummers were known to be killed or wounded. Charley King, a famous drummer for the 49th Pennsylvania Regiment, died of wounds suffered at the Battle of Antietam when he was only 13 years old. He enlisted in 1861 and was considered a veteran because he served during the Peninsula Campaign in early 1862 before he experienced a minor skirmish previous to the field at Antietam. Although his regiment was still in the rear, a stray Confederate shell exploded overhead, and a shrapnel landed down into the Pennsylvania troops. King, severely wounded having been struck in the chest, died in a field hospital three days later. He was also the youngest casualty at Antietam.

See: Facts About Civil War Drummers; Drummer Boys: A Myth and A Worker – Stony Brook Undergraduate History Journal

Over 40,000 minors served in the Civil War; how many were drummers is unknown. These are the factors Google claims that led to their demise:

- Even though they were not the front line fighters, they were positioned near the front lines anyway to communicate orders and were vulnerable to enemy fire.

- As you can imagine, without them, there would be no communication to the troops and morale would drop, so they were definitely targeted.

- Diseases would affect them as they would all the other soldiers; it was known to ravage armies during the Civil War

However, the use of drums on the battlegrounds declined through the years but continued to be seen marching in military parades. But what makes a drummer want to march in these celebrations or, for that matter, parades on the whole? Or how about playing the drums in the first place? To begin with, it’s passion. Needless to say, each and every drummer loves to play drums. They don’t play them because they have to. Many start at a very young age. They might begin by pounding pots and pans on the kitchen floor and communicating their feelings that way. It was more than fun, the child was expressing his emotion, releasing his energy. The drummer discovered he can easily connect with people across various backgrounds and generations. They know this, they make it happen, and they watch it happen. Drummers have much power from the bandstand and even in battle.

The drummer, him- or herself, is also the backbone of a band. He plays with authority and has the responsibility of guiding the band’s rhythm. Through his playing and persistence, he has developed a personal growth, and this shows in the level of his playing excellence. Science via imaging and other technical ways has shown the development of strong cognitive processes and auditory information that’s translated across the brain which allows the drummer to consistently perform his rhythm. This is rhythm accuracy — a steady beat. The drummer uses multiple areas of his brain to produce rhythm. Plus, neuroscientists are now using drumming and the power of rhythm for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s patients for brain repair. It helps to remind people of memories of their past.

Here is a quote that is making me want to move back into my bigger house, after “downsizing” so I have a place to put a new set of drums. It was here, a couple of years later, in our smaller home that I was diagnosed with PPMS and I have already begun to see cognitive changes. Perhaps learning to play the drums, instead of the banjo that I played for two years, is the way to go. Now, where was I? Oh, yes, the quote:

Research published in the Journal of Neuroscience found that professional drummers have different brain structures compared to non-musicians. They showed increased white matter in the corpus callosum, the bundle of nerve fibers that connect the two hemispheres of the brain. This suggests that drumming can actually strengthen the connections between different parts of our brain, leading to improved cognitive function across the board.

Another study, conducted at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, found that drummers who kept a steadier rhythm had different white matter structure in their brain. This indicates that the act of maintaining a steady beat could be physically changing the structure of our brains, potentially leading to improved cognitive abilities.

It’s not just about physical changes in the brain, though. The cognitive benefits of drumming are wide-ranging and impressive. From improved coordination to enhanced memory, the “drum brain” phenomenon is proving to be a powerful tool for cognitive enhancement.

See: NeuroLaunch.com: Where Grey Matter Matters

Making the drum be heard is also a cardiovascular workout. It’s a physical healthcare tool for the drummer as well as the listener. Tests revealed that drummers burn more calories than one would while hiking, skiing, swimming, and rowing. On the other hand, the consistent tempo induces a meditative state for the listener; the resultant sensation is one of lightness, freedom, and a calm mentality. Try sitting back and concentrating on a low, smooth drumbeat. See what happens to you. (I’m falling asleep just reading this about it.)

Drumming promotes strengthening of the muscles used in the act of playing for the drummer and enhances greater control of his hands and feet. There is an increase in endorphins, and the boost of these endorphins leads to a positive degree of mental health. Drummers use less pain killers because of the release of these therapeutic endorphins. (This is a type of endorphins your body produces naturally that are morphine-like chemicals that reduce pain and stress; they promote feelings of pleasure and well-being.) Also, the activity of drumming itself has been shown to increase the production of natural T-Cells in the body. These T-Cells begin inside your bone marrow. They move to tissues and organs in your lymph system (spleen, tonsils and lymph nodes) and circulate in your bloodstream and are on standby until you need them for protection. It is the T-Cells, the specialized white cells that are known to seek out and fight cancer cells, etc. (Hmmm. Does Medicare cover the cost of drums? There could be group-drumming therapy sessions to reduce stress! How fun! All you’d need is an instructor to volunteer to teach it. Right?) So, “could be”? Oh, no! Last night, watching Netflix, and what do you think? There it was, and well into the storyline, the protagonist Fleur in the movie Tuiscoms, episode dubbed “The Persistence of Memory,” (I first discovered this caption today, 9-13-25, two weeks after I wrote this blog and decided to research the movie’s name for you) comes upon the town’s party where all were seated around – maybe 15 townsfolk – each playing their own drum, laughing up a storm, begging her to join them. I was flabbergasted again knowing my ESP was at work at the timing because I just wrote about this the day before I saw it on TV! This is not the first time this has happened to me. Ask me about the small watermelons…. Backing up, now that I think about it, the writer of this story must have known about the wonders of the drumbeat working with one’s memory. And before I go on, I just discovered, merely by driving by and seeing a sign outside the building, that In Sun City West, AZ, there are five fitness clubs that offer cardio drumming classes! Am I really the last to learn about the positive health effects of cardio drumming? Thank you, Bart Haynes, for sending me in the right direction.

Sorry, I digressed. Okay. Back to drums and drummers. We know along with the drums, music gave us the means to connect when it came to a time of anti-war expression. For instance, our country was split apart over the war in Vietnam; it involved something that not everyone agreed upon, that we should not become involved or that our men should be sent away to help stop the spread of communism.

Still, as our soldiers marched into battle, and protesters filled our streets, music provided a voice for the voiceless and a means of expression for the disillusioned about the Vietnam war – that it was all too much for our lyric writers; they did not hold back telling how they felt. Lyrics of iconic songs still echo to this day telling the sentiments of anti-war activists while at the same time offering comfort to those fighting on the front lines. Internet sites list different songs on their top 10 list. One site lists these as their top 10 famous songs written during that tumultuous time:

“We Gotta Get Out of This Place” by The Animals

“I Feel Like I’m Fixin to Die Rag” by Country Joe & The Fish

“Leaving on a Jet Plane” by Peter, Paul and Mary

“Detroit City” by Bobby Bare

“Purple Haze” by Jim Hendrix Experience

“Fortunate Son” by Creedence Clearwater Revival (CCR)

“(Sittin’ on) The Dock of the Bay” by Otis Redding

“The Letter by The Box Tops”

“Chain of Fools” by Aretha Franklin

“Green Green Grass of Home” by Porter Wagoner

Yes, and there are many, many more. And you can put your own meaning to these lyrics, but if you research, there are specific and heavy thoughts put into these words. The time was sad for all the writers.

While the youth were expressing themselves and our country was in a sort of chaos about the Vietnam war, I was a court reporter in federal court, and our calendar was clogged with conscientious objectors’ hearings who claimed exemption from military service. They based this on personal beliefs – usually religious convictions, but also passivism, and flat out moral opposition to the war. Some received rulings that were granted, some denied. Of those denied, many applicants who refused to submit to the induction bureau faced legal consequences — they were severely fined or imprisoned for non-compliance with the draft laws, with penalties under the Military Selective Service Act. Within their community, they faced ostracism, being labeled cowards or traitors, and whatever the community had in store for them.

At the time, there were quite notable movements and people within them. The prominent figures who emerged during this time were: Muhammad Ali, the renowned boxer who refused induction in 1967, citing his religious beliefs as a Muslim and also his opposition to the war. He was arrested and stripped of his boxing titles. Other movements were made by the Berrigan Brothers — Philip and Daniel Berrigan, who were Catholic priests and prominent anti-war activists. They led protests and acts of civil disobedience; the Catonsville Nine, of whom the Berrigan Brothers were members, publicly burned draft records as a form of protest; the Camden 28, which resulted in a three-month long trial, and for this trial I was the court reporter and can remember the highly publicized testimony by the 28 defendants and their witnesses and the judge’s charge and reaction, and the jury’s reaction with their “not guilty” verdict to their felony charges for burning their draft cards. That told of the public opinion of the moment. There was also the Vietnam War Resisters League, founded in 1923, which arose again here and demonstrated against the Vietnam War.

Many people at the time who were opposed to the war, either before or after being drafted, just left the country. Some are still in Canada today.

Needless to say, there were a number of musicians who were drummers who either served in the Vietnam War or were performers requested by the government to entertain the troops. Some drummers played in bands outside of the service who quit and joined the military on their own and others belonged to bands as a whole who were sent to Vietnam to entertain the troops. Many of these musicians and drummers died overseas. Yes, they were killed in the war either because they were drafted, or they enlisted on their own accord, or played for our troops at our request. Here are a few I will address now, in alphabet order. Remember, it is only a sample.

Thomas Drum

Tom was a native New Yorker who was drafted into the army and served his tour as a Specialist Four. As an Infantryman, he was assigned to the 62nd INF PLT CBT TRACKER 1ST CAV DIV. During his service, on March 4, 1970, Tom experienced a hostile action receiving multiple fragmentation wounds in South Vietnam at Tay Ninh province which ultimately resulted in his death. There isn’t much else written about Tom except a couple personal statements from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall site:

Tom was my friend. It is amazing how one 15 year old can change an entire class. Tom had such class and style…he was a natural born leader. It was an unnecessary loss to take him from this world so early.

I remember his smile, his laugh and him walking down the street with his derby, top coat and umbrella…I think he taught all of us about being open minded, fair and kind…and it has stayed with me all of these years.

POSTED BY: Combat Tracker Teams of the Viet Nam War

COMBAT TRACKER – 62nd IPCT- 1st CAV

God bless you for your honorable service as a Combat Tracker

He was a natural born leader. I can only imagine what impact he would have made on the world, if he had the opportunity to live out his life.

POSTED BY; Mary Quattrone May 28, 2012

He was awarded the Bronze Star medal for Valor and a Combat distinguishing Device (V) for his exemplary gallantry in action. Tom was also awarded the Bronze Star Medal for Merit for his sustained meritorious service, plus a Purple Heart. Amongst those awards, Tom received a Combat Infantryman Badge, a Marksmanship Badge, a National Defense Service Medal, a Vietnam Campaign Medal, the Vietnam Service Medal, an Army Presidential Unit Citation, and a Vietnam Gallantry Cross.

Bart Haynes

As a teenager, Bart was a member of The Castiles rock band in Freehold, New Jersey. In 1965, a 15-year-old guitarist named Bruce Springsteen joined their group. The band became popular as they played all around central New Jersey. A bandmate remembered him as an “absurdly funny kid, classic class clown, and a good drummer with one strange quirk: couldn’t play ‘Wipe Out’ by The Surfaris.” Bart was very energetic and enthusiastic about everything he did, and he decided he had to do more, and as the personality of a drummer, he had the power to change his life.

So, in April of 1966, after graduating high school (some notes say he quit), he left the Castiles and joined the Marines in October, he found himself in Vietnam.

On his last visit home, Bart had this premonition, he told his friends and family members that he wouldn’t return alive. Unfortunately, he was correct, and on October 22, 1967, Bart was killed by mortar fire in Quang Tri Province in Vietnam. He was the first soldier from Freehold, New Jersey, to die in the Vietnam War. The awards Bart received were the Purple Heart, Combat Action Ribbon, National Defense Service Medal, Vietnam Service Medal W/Star, and the Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal.

Bart’s Purple Heart, Bruce Springsteen Archives & Center for American Music,

Melissa Ziobro, Curator.

Photo source: Barton Edward Haynes : Lance Corporal from New Jersey, Vietnam War Casualty

Leo Hampton

Leo Hampton was a Navy musician and drummer who served in World War II and was honored by other Navy musicians in 2025. Although Leo was not killed in Vietnam, he was indeed a drummer and he popped up in my research and should be remembered here in case he was not remembered elsewhere as a drummer. Leo lost his life fighting in a war for representing the United States. He was remembered on Facebook as such: “Remembering Lionel Leo Hampton (April 20, 1908 – August 31, 2002) was a jazz vibraphonist, drummer, percussionist, and bandleader. Hampton worked with jazz musicians from Teddy Wilson, Benny Goodman and Buddy Rich to Charlie Parker, Charles Mingus, and Quincy Jones.” Let’s not forget Leo who gave his life for us.

Richard Arnold Johnson

Richard was from Escanaba, Michigan, and was born on January 20, 1947. He was drafted into the army and entered via the Selective Service beginning January 28, 1967, with the rank of Specialist Four. His military specialty was Light Weapons Infantry attached to 9th Infantry Division, 3rd Battalion, 47th Infantry, A Company. Richard died May 7, 1967, as a result of a bullet penetrating his heart from a hostile booby trap round during a combat operation in the Mekong Delta region of South Vietnam. It was attributed to hostile activity, ground casualty, at South Vietnam, Dinh Tuong province.

His awards consist of the Purple Heart, the Combat Infantryman Badge, the Marksmanship Badge, the National Defense Service Medal, the Vietnam Campaign Medal, the Vietnam Service Medal, the Army Presidential Unit Citation, and the Vietnam Gallantry Cross. I could not find anything about his playing an instrument or anything more about him. So, I inquired into the internet generally, and a response was that he played the saxophone and piano, although he was initially found when I searched for “drummer.”

Source for both images: Ghosts of the Battlefield’s Post; Remembering Fallen Hero

Richard Arnold Johnson in the Vietnam War

Rick Linton

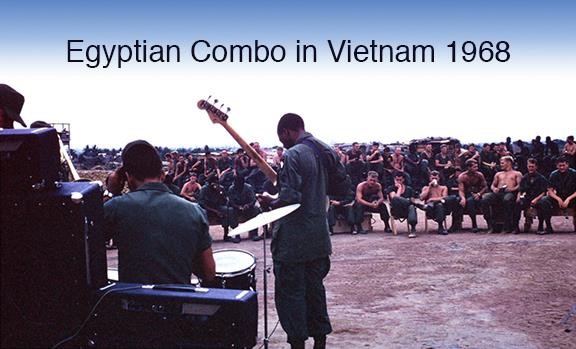

Rick Linton, a drummer, along with Phil Willis and Kurt Pill, and a member of a group of Illinois musicians, was recruited to play for Vietnamese villagers and U.S. troops to help win the war. Rick Linton had a long career with the Egyptian Combo, a band formed in the early 1960s.

The band was formed in Herrin and originally featured six members: Doug Linton, Butch Nevious, Rick Linton, Lonnie Dixon, Lloyd Rainey, and Nick Ridgeway. There was some to-do over changing their name, and Linton thinks military brass made them change the name “to promote the army,” although Nevious insists it was the musicians’ idea. Later, they became the Screaming Eagles Combo.

Source: (20+) Facebook

William “Butch” Nevious

William “Butch” Nevious was the percussionist in the Screaming Eagles Combo and ended up in South Vietnam during the final months of 1967. They performed for troops as well as villagers as part of an Army initiative to boost morale. Nevious claimed he just grabbed his drum kit from the back of the truck when he knew this wouldn’t be a typical gig. When he and his fellow band members weren’t on kitchen duty, guard patrol, or setting aflame oil drums full of human waste, they’d be driven or flown to what his bandmate Rick Linton calls “bases and shitholes,” some in the middle of the Vietnamese jungle. Lloyd Rainey, Rick Linton, Ellis Mc Kenzie and Butch Nevious were part of the 101st Airborne Division (all from Southern Illinois). “We covered most of Vietnam in two Huey helicopters and entertained the troops at fire bases, med-evacs, airbases and ships throughout the country in 1967 and 1968. Sargent Danny Jaynes was our Manager/Officer in charge. Although we were not supposed to be combat soldiers, we were part of the parameter guard during the Tet Offensive at Bien Hoa Airbase when it was overrun by an NVA battalion for which we were awarded the bronze star.” The group also received the Army Commendation medal for their service as the Combo.

See: (20+) Lloyd Rainey, Rick Linton, Ellis Mc Kenzie… – The Egyptian Combo | Facebook

The Screaming Eagles Combo were a group of Illinois musicians, including drummer Rick Linton, who were recruited to play Motown for Vietnamese villagers and U.S. troops to help win the war.

In 1967-68 the Screaming Eagles Combo aka Egyptian Combo was flying from base camp to base camp entertaining the soldiers in Vietnam –

four from Southern Illinois along with five other great musicians. Left to right: Wesley Jones, Eddie Owen, Ellis Mc Kenzie, Royce Patterson, Bobby Perino, Lloyd Rainey, (front row) Rick Linton, Terry Stewart, Butch Nevious. Photo was taken in Hue, Vietnam.

Eddie Owen, Rick Linton, Lloyd Rainey, Terry Stewart, and Ellis McKenzie (from left) in Vietnam, 1968. The soldiers were tasked with playing music, not just for U.S. troops, but for Vietnamese villagers.

Source both photos: (20+) Facebook

Phil Willis and Kurt Pill

Phil Willis (18) and Kurt Pill (17) were members of the group Brandi Perry & The Bubble Machine. They were one of the bands who traveled overseas to entertain the troops in Vietnam. In this band, none of them were older than 20. They were there for less than a month when their vehicle was attacked. It was July 5, 1968, when their truck left Saigon for Vung Tau near the end of the day and was halfway to their destination when they were ambushed from the side of the road by Vietcong sympathizers.

The attack caused the truck to run off the road and turn over into a ditch. The drummer and keyboard player — Phil Willis (drums) and Kurt Pill (keyboards) — both only 17 years old, were killed when South Vietnamese troops opened fire on their van (while, ironically, their set listed to play for that nite the well-known Vietnam recording “We Gotta Get Out of This Place.” The survivors, Jack Bone and Brandi Perri. lived only because, SP4 David K.Hamilton U.S. Army, who was assigned to the HQ Company, after their truck turned over into a ditch, ordered them to stay still and play dead so the enemy wouldn’t kill them. Saigon newspaper reports indicated that investigations showed that the group was ambushed from both sides of the road by “an unknown-sized enemy force, presumably Viet Cong.”

Image Source: Brandi Perri and the bubble gum machine vietnam – Search

Gary Salt

Gary Salt is a drummer who performed in the US Army’s 1st and 25th Infantry Division bands during his service in Vietnam. He served at Ft. Bragg from October 1967 until June 1969, and then he served in Vietnam for a year initially with the 1st Infantry Division (Big Red One). This picture below was taken seven days after he had begun basic training. He’s one pictured in the bottom right beside the soldier with the white helmet. He says, “It should be obvious by my poise, my smile and my appearance I really did not want to be there.

Every division had a band,” Salt said. “We used to travel in Deuce and a half trucks–open back trucks–and we would go out to the villages and play for the villagers. That was one of our duties. Also, we would play for military ceremonies. We were close to Saigon so we’d go down and give concerts there. Then we would go out into the field and entertain the troops. That was our duty: to win the hearts and minds of people. Actually we’d go with the intelligence team, medical team, and dental team–we’d all go out in a convoy. We’d be playing while the doctors and dentists were trying to treat people and the intelligence people were trying to get as much information as they could.”

When he came back from Vietnam, Salt said he decided to put the drums on hold and get his education.

But I made it through basic and was assigned to the 440th Army Band at Ft. Bragg. until June of 1969.” Then he was assigned to the 1st Infantry Division Band in Vietnam. Later Gary was reassigned to the 25th Division Band after the 1st Division was the first division to be pulled out of Vietnam in 1970. He left Vietnam on July 1, 1970, and was released on July 3 in Oakland, CA.

We were the headquarters band, kept very busy playing ceremonies, change of commands and concerts.

Gary Salt played for President Lyndon B. Johnson during his service in the U.S. Army Band in Vietnam, the Vietnamese inauguration. within the confines of the area of the 1st Infantry Division at some remote village circa 1969 with a member of the 1st Division Army Band. “Our assignment was to help win the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese people. We certainly tried.”

After his military service, he put drumming on hold to get an education but later returned to music. But at age 75, Salt said he still wants to further his knowledge of drumming and percussion and was clear about his direction: “I can’t stop.”

Fancy drums and their glamorized drummers throughout history began to march in our extensive military parades. The role of drummers communicated the commands of their leaders and carried the voices of the protesting people of the day. These thinkers wrote the lyrics into their favorite anti-war tunes, and the drummers beat their rhythm into the hearts of all those who heard it. They shouted, these people danced to the beat, and many of them marched to the rhythm of the underlying drumbeat. Often chaos was collected into one direction – the hope of peace.

The protest songs of the Vietnam era — voiced by Lennon, Seeger, Dylan, Springsteen, and all others — were more than melodies; they were elegies for the fallen, especially the drummers who once kept time and then marched off to war, many never to return. Those lyrics weren’t written lightly — they were poured out in grief, in rage, in disbelief at the cost of it all. And behind those words, the beat of the drummer echoed still, a pulse of remembrance and resistance. Today, if you listen closely and read between those heavy lines, you’ll feel the ache and urgency of a generation asking, “For what?” So, tap your foot, or better yet, rise up and march—not just to the drumbeat, but to the memory. Dance to that different drummer.

See: The Role of Music in the Vietnam War Era; The Sixties and Protest Music | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History; https://americansongwriter.com/8-songs-that-defined-the-protest-movement-of-the-1960s/

by Lynne T. Attardi